Is Empathy a Sin?

The “Empathy is a Sin” Movement

Imagine sitting in church one Sunday, expecting a sermon on love and compassion, and instead, the pastor warns you that empathy is dangerous—maybe even sinful. That’s exactly what some Christian leaders, like Doug Wilson, are preaching. They argue that empathy leads people away from truth and into emotional compromise. Their claim? Feeling deeply for others makes you susceptible to sin because it clouds your judgment.

Now, take a second and let that sink in. If empathy—the ability to step into someone else’s pain and understand their suffering—is a sin, what does that say about Jesus?

Jesus didn’t just tell people He loved them from a distance. He wept with them. He touched the untouchable. He entered into people’s suffering, even when it was messy and inconvenient. He didn’t just feel for people; He felt with them.

So why are some pastors suddenly pushing this idea that empathy is dangerous? And what does it say about the state of modern Christianity?

This post isn’t just about debunking a theological argument—it’s about recognizing how dangerous this mindset is. Teaching people to suppress empathy doesn’t just twist scripture; it makes them more susceptible to manipulation, abuse, and emotional detachment.

Let’s break it down. First, we need to talk about how this argument is redefining empathy, why that redefinition is misleading, and how it’s being used to shift power dynamics in the church.

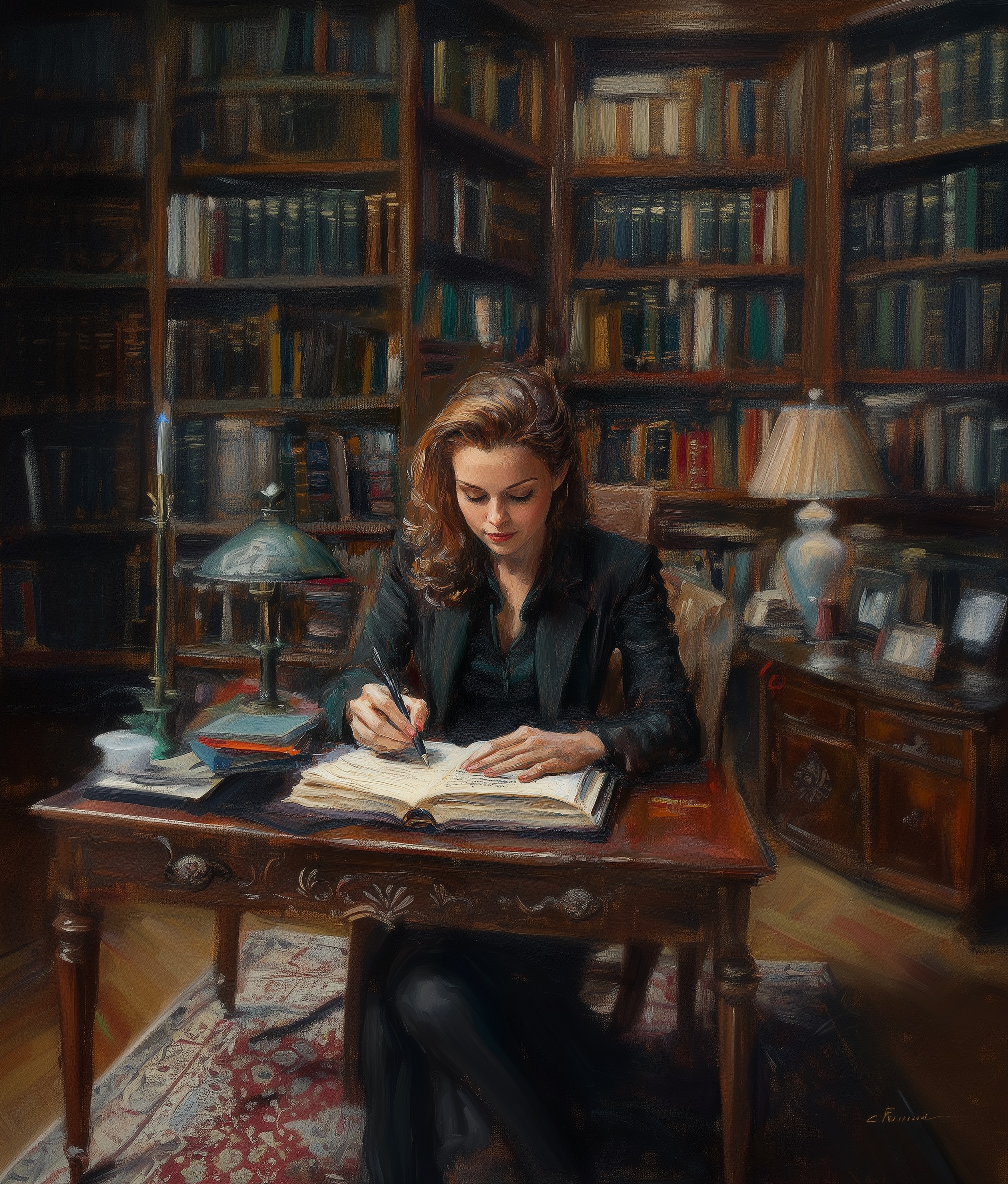

Understanding Empathy vs. Sympathy

If you’ve ever taken a psychology class, you’ve probably heard the difference between sympathy and empathy.

- Sympathy is when you feel sorry for someone from a distance—like when you see someone struggling and say, “That’s tough. I hope things get better for them.”

- Empathy is when you actually step into someone’s pain, trying to understand what they’re going through—like when you sit with a grieving friend, listen to their story, and say, “I can’t imagine how hard this must be for you.”

One acknowledges suffering from the outside; the other enters into it.

Now, here’s where pastors like Doug Wilson come in. Instead of defining empathy the way psychologists and everyday people do, they redefine it as an emotional trap—something that makes you lose your ability to think clearly and stay grounded in “truth.” According to them, if you let yourself truly feel someone else’s pain, you risk being manipulated into agreeing with their perspective, even if it’s sinful.

That’s why Wilson argues that sympathy is okay but empathy is dangerous. Sympathy allows you to care without getting “sucked in,” while empathy supposedly leads you away from righteousness.

But here’s the problem: That’s not how Jesus operated.

If we accept this twisted definition of empathy, we have to ignore huge portions of Jesus’ ministry—times when He wasn’t just an observer of suffering, but an active participant in it. If empathy is sinful, then by their logic, Jesus Himself sinned.

So, let’s put this claim to the test: Did Jesus show mere sympathy, or did He practice true empathy?

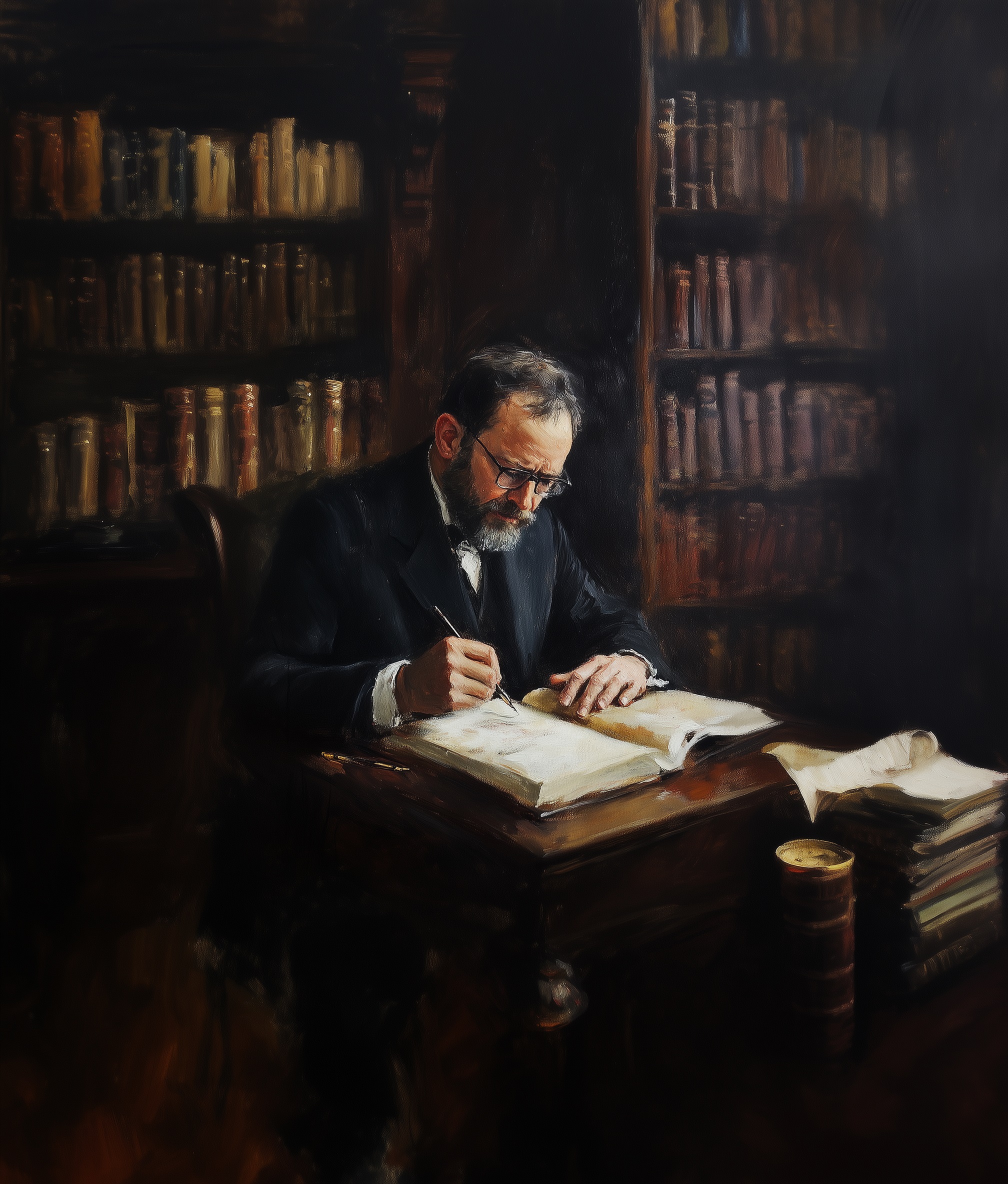

Jesus and Empathy: Did He Feel With or Just For?

If empathy is truly dangerous, then we should expect to find Jesus keeping a safe emotional distance from suffering people, right? He should have been the ultimate example of detached sympathy—acknowledging pain but never really stepping into it.

But that’s not what we see. At all.

Let’s break down a few key moments where Jesus fully entered into human suffering:

Jesus Weeping with Mary and Martha (John 11:32-35)

When Jesus arrived at the home of Mary and Martha after their brother Lazarus had died, He didn’t just stand at a distance and say, “Don’t worry, I’ll fix this.” Even though He knew He was about to raise Lazarus from the dead, He stopped and wept.

He wasn’t crying because He lacked faith—He was feeling their grief. He entered into their pain, fully present with them in their suffering. That’s empathy, not distant sympathy.

The Good Samaritan: A Lesson in True Compassion (Luke 10:30-37)

The parable of the Good Samaritan isn’t just about helping people—it’s about deep, inconvenient, costly empathy. The religious leaders in the story saw the injured man and walked past him. They might have even felt sorry for him (sympathy) but did nothing.

The Samaritan, on the other hand, didn’t just acknowledge the man’s suffering. He stopped, tended his wounds, and paid for his care. He put himself in the injured man’s position and acted accordingly. That’s what empathy looks like.

Jesus Healing the Sick and Touching the “Untouchable”

- He touched lepers (Mark 1:40-42) when no one else would go near them.

- He let a bleeding woman touch Him (Mark 5:25-34), even though it made Him ceremonially “unclean.”

- He ate with sinners (Matthew 9:10-13), fully engaging with people society rejected.

Jesus didn’t just observe suffering and offer words of encouragement from a safe distance—He stepped into people’s pain, no matter how messy it was.

Now, here’s the real question: If Jesus modeled this kind of radical empathy, why are some pastors teaching that it’s sinful?

That brings us to the real issue—control. When you can convince people to suppress their natural empathy, you make them easier to manipulate. Let’s talk about the psychological consequences of rejecting empathy.

The Psychological Impact of Rejecting Empathy

Let’s step back for a second and think about what happens when someone is told that empathy is dangerous. If you’ve grown up in a church that preaches this message, you might not even realize the ways it’s shaping your emotions, relationships, and even your mental health.

At its core, empathy is what allows us to connect deeply with others. It helps us understand people’s struggles, support them in meaningful ways, and build strong, compassionate communities. When you strip that away, something shifts—not just spiritually, but psychologically.

What Happens When You Suppress Empathy?

You Become Emotionally Detached

If you’re constantly told that feeling another person’s pain too deeply is dangerous, you start to put up walls. You hear someone’s struggles, but instead of engaging, you distance yourself. Over time, this can lead to emotional numbness—not just toward others, but even toward yourself.

You Struggle to Form Deep Relationships

Empathy is the glue that holds relationships together. If you’re conditioned to keep emotional distance, even from people in pain, you might find it harder to form genuine, intimate connections. Friendships and marriages suffer when one or both people have been taught to avoid emotional engagement.

You Become More Susceptible to Black-and-White Thinking

Empathy allows for nuance—it helps you see the complexity of human experiences. When empathy is suppressed, it’s easier to fall into rigid, black-and-white thinking: “This person is right; that person is wrong. This group is good; that group is evil.” You don’t take time to understand people’s experiences because you’ve been trained to prioritize “truth” over feelings.

You Become Easier to Control

And here’s the big one. If you can be convinced that empathy is sinful, then leaders can tell you exactly how to think and feel. When you hear about someone’s suffering—whether it’s a victim of church abuse, a marginalized group, or even a friend struggling with doubt—you’re trained to dismiss their emotions rather than engage with them. This makes it easier for toxic church structures to silence dissent and maintain power.

Think about it: If people in these churches fully embraced empathy, they might start asking hard questions. They might start listening to the experiences of LGBTQ+ people, abuse survivors, or those hurt by church teachings. They might realize that some of these “outsiders” aren’t lost sinners, but people who have been deeply wounded by the very institutions claiming to love them.

And that’s a problem for those in power. So, when a pastor like Doug Wilson tells his congregation that empathy is dangerous, what he’s really saying is:

- “Don’t listen too closely to people who are hurting.”

- “Don’t question the church’s authority just because someone shares their pain.”

- “Don’t let your emotions interfere with what we tell you is the truth.”

This is where the danger lies. It’s not just about one theological debate—it’s about controlling how people feel, think, and respond to suffering.

And when you strip away empathy, you create a church culture where abuse thrives, suffering is ignored, and blind obedience is praised as faithfulness.

So, let’s get to the real question: Who benefits from demonizing empathy? And why is this message gaining traction in certain church circles?

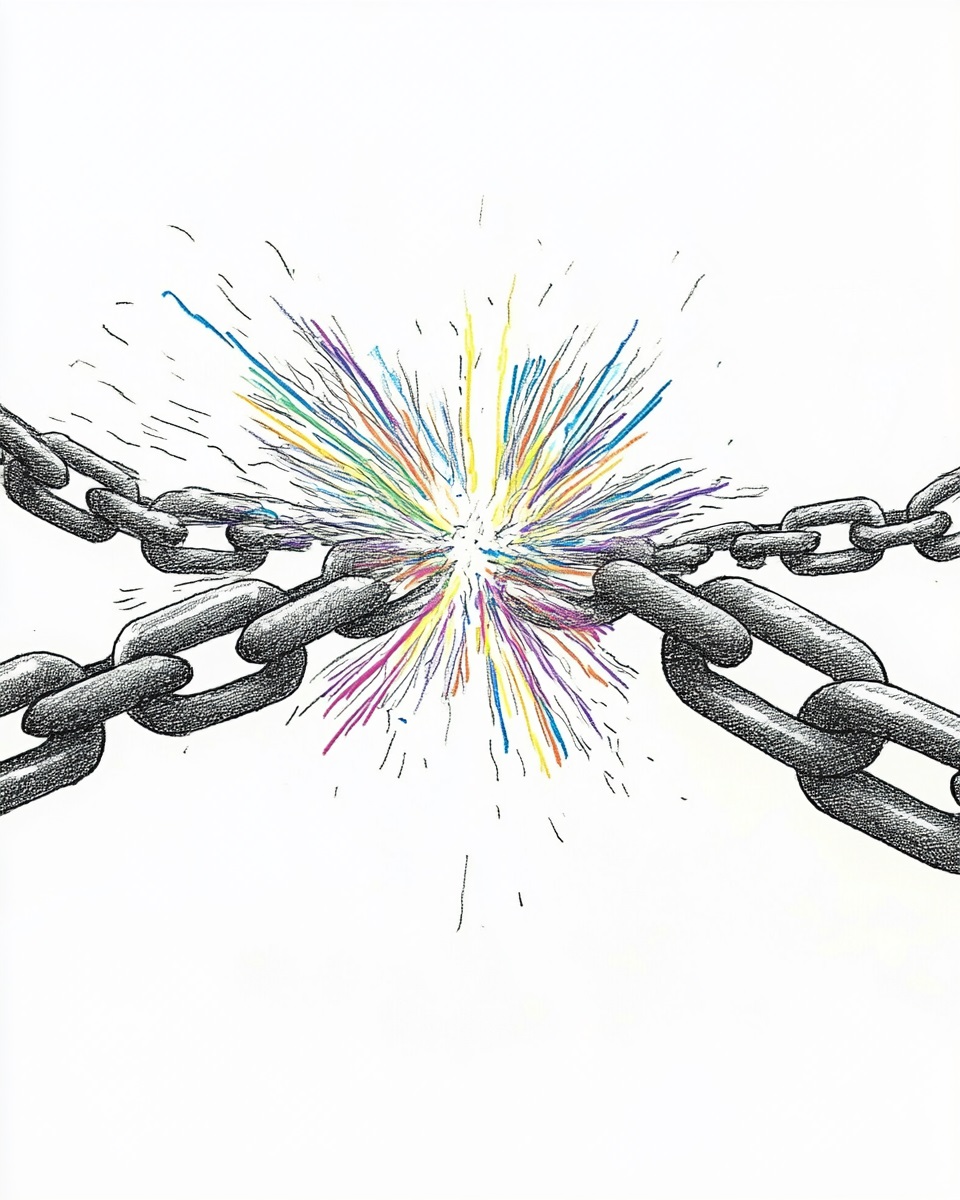

Why This Theology is Dangerous

Let’s be real—if a pastor tells you that empathy is sinful, the first question you should ask is: Who benefits from this?

Because it’s certainly not the people who are hurting, questioning, or searching for support. It’s not the victims of spiritual abuse. It’s not the people struggling with mental health, doubt, or personal crises.

So, who does benefit?

Church Leaders Who Want Unquestioning Obedience

If pastors can convince their congregations that empathy leads people away from truth, then they can also convince them that listening too much to other people’s pain is spiritually dangerous.

That means:

- When someone speaks up about being hurt by the church, their emotions can be dismissed as “worldly influence.”

- When marginalized communities express their suffering, Christians are taught to resist engaging with them emotionally.

- When people start questioning harmful theology, they can be labeled as being “too emotionally driven” instead of pursuing “biblical truth.”

By demonizing empathy, pastors create a safeguard against dissent. It keeps people from questioning harmful teachings because they’ve been conditioned to ignore the voices of those who have suffered under them.

Systems That Prioritize Ideology Over Humanity

Many fundamentalist and evangelical churches function on rigid theological systems—and rigid systems require compliance to survive.

If empathy is allowed to flourish, then people might start challenging those systems:

- “If my LGBTQ+ friend is suffering under church teachings, maybe the problem isn’t them—maybe it’s the theology.”

- “If victims of church abuse keep speaking out, maybe we need to rethink how we handle power and accountability.”

- “If deconstruction stories are so common, maybe we should ask why people are leaving rather than just condemning them.”

But these are dangerous questions for churches that rely on absolute control. So, instead of engaging with them, leaders shut down the conversation before it even starts by telling their followers that empathy itself is a trap.

A Culture That Punishes Emotional Honesty

When empathy is painted as a sin, feeling deeply becomes a spiritual liability. This means that:

- People start suppressing their own emotions, leading to shame, guilt, and anxiety.

- Vulnerability becomes risky, because being “too emotional” might get you labeled as weak or easily deceived.

- People who naturally feel things deeply—whether through compassion, grief, or righteous anger—start questioning if something is wrong with them.

This is where mental health takes a major hit. When people are taught that their feelings are a threat to their faith, they learn to distrust their own emotions—which can lead to anxiety, depression, and even trauma responses.

Why This is So Dangerous

A faith that suppresses empathy is a faith that lacks true compassion. And a faith that lacks true compassion is a faith that enables harm.

When Christians are told to keep emotional distance from suffering, they stop seeing people as complex, hurting humans and start seeing them as theological problems to be solved or ideological threats to be resisted.

And that is the exact opposite of what Jesus modeled. So, if rejecting empathy leads to emotional detachment, control, and a lack of compassion… then what should we do instead? That leads us to the final point—how do we reclaim empathy as a strength instead of seeing it as a weakness?

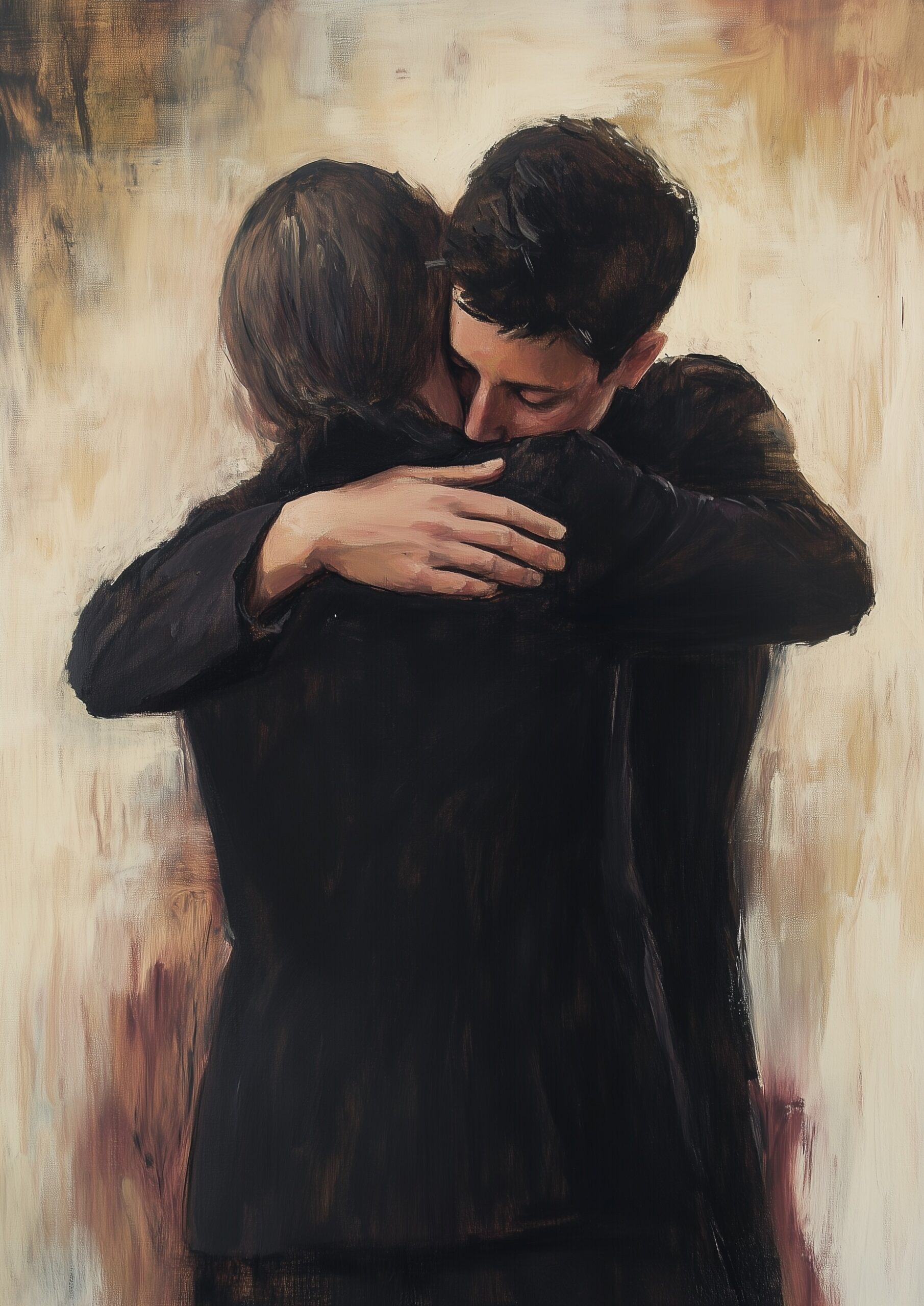

Reclaiming Empathy: A Call to Love Fully

If you’ve ever been told that empathy is dangerous, sinful, or a sign of weakness, I want you to hear this loud and clear: Empathy is not a flaw—it’s a strength.

Empathy is what allows us to love in the way Jesus commanded. It’s what makes relationships meaningful, communities stronger, and justice possible. Without it, we don’t just lose our ability to care—we lose our ability to truly connect.

So, how do we push back against this harmful teaching and reclaim empathy as a core part of faith and humanity?

Recognize That Empathy and Truth Are Not Opposites

One of the biggest lies in this anti-empathy movement is that you have to choose between empathy and truth—as if feeling deeply for someone automatically means abandoning reason. That’s simply not true.

- You can empathize with someone struggling with their faith without compromising your own beliefs.

- You can listen to an abuse survivor’s story without assuming they’re exaggerating or “attacking the church.”

- You can stand with marginalized people without abandoning your convictions.

Empathy doesn’t mean agreeing with everything someone says—it means caring enough to listen, understand, and respond with compassion.

Set Boundaries, But Don’t Shut People Out

Now, some people might ask, “But what if empathy becomes overwhelming? What if someone manipulates my emotions?” And that’s a valid concern. Healthy empathy includes boundaries. But boundaries don’t mean shutting off your emotions completely. They mean knowing when to care deeply without losing yourself in someone else’s struggles. For example:

- If a friend is going through something hard, you can listen and support them without taking responsibility for fixing everything.

- If someone’s pain triggers your own trauma, it’s okay to step back and take care of yourself while still caring about them.

- If a church leader tells you to ignore someone’s suffering in the name of “biblical truth,” that’s not a boundary—that’s emotional suppression.

Empathy doesn’t mean absorbing everyone’s pain—it means acknowledging it, responding with care, and knowing when to step back for your own well-being.

Challenge Churches That Teach Emotional Suppression

If a church tells you that empathy is sinful, it’s worth asking: Why are they so afraid of people feeling deeply?

- Are they worried that if you empathize with certain groups, you’ll start questioning church teachings?

- Are they trying to protect their power by keeping people emotionally disconnected?

- Are they dismissing victims of harm because addressing their pain would require change?

A healthy faith welcomes questions, feelings, and human connection. Any church that tells you to shut down your emotions isn’t protecting truth—it’s protecting control.

Embrace Empathy as Part of Your Spiritual and Emotional Growth

Empathy makes us more human. It helps us become better friends, better partners, better leaders, and better people. And if you come from a faith background that taught you to suppress it, reclaiming empathy might feel both freeing and scary at the same time. But here’s the thing—real love requires risk.

- It requires listening instead of shutting down.

- It requires sitting with pain instead of rushing to fix it.

- It requires engaging with people’s struggles instead of dismissing them as “too emotional.”

That’s the kind of love Jesus modeled. And that’s the kind of love that can change lives.

Final Thoughts: Choosing Connection Over Control

If you take one thing away from this conversation, let it be this:

Empathy is not a sin. Emotional detachment is not a virtue. And any theology that tells you to suppress your compassion is one that should be questioned.

The world doesn’t need more people who can recite doctrine but lack compassion. It needs more people willing to feel, connect, and love deeply—just like Jesus did.

So, if you’ve ever been made to feel guilty for caring too much—for crying with a hurting friend, for questioning a church’s treatment of marginalized people, for listening to someone’s pain and truly feeling it—you are not wrong for caring.

You are not sinful for feeling deeply.

You are human. And that is a beautiful, necessary, and powerful thing.